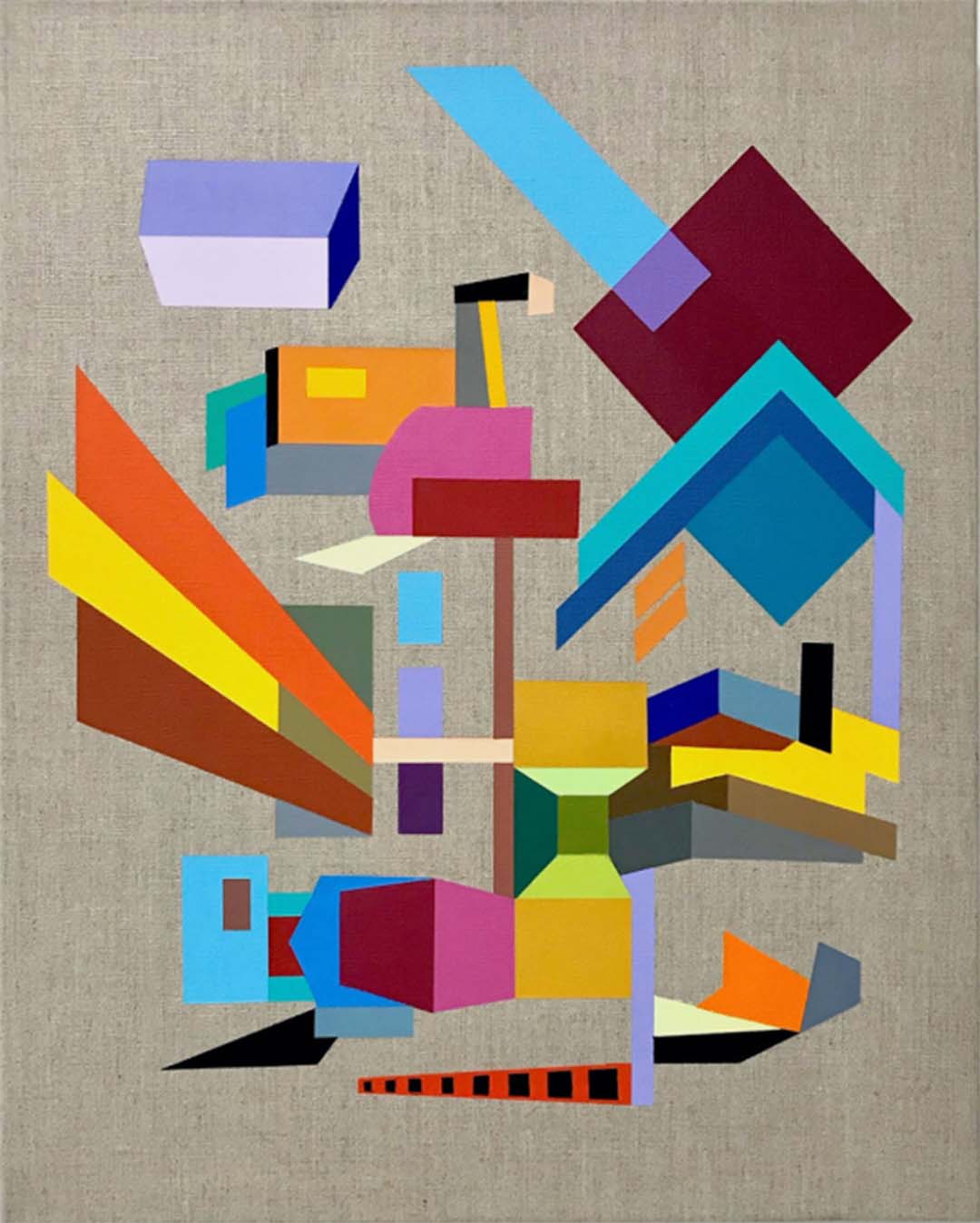

Carrie Moyer Bronzing in Paradise, 2022

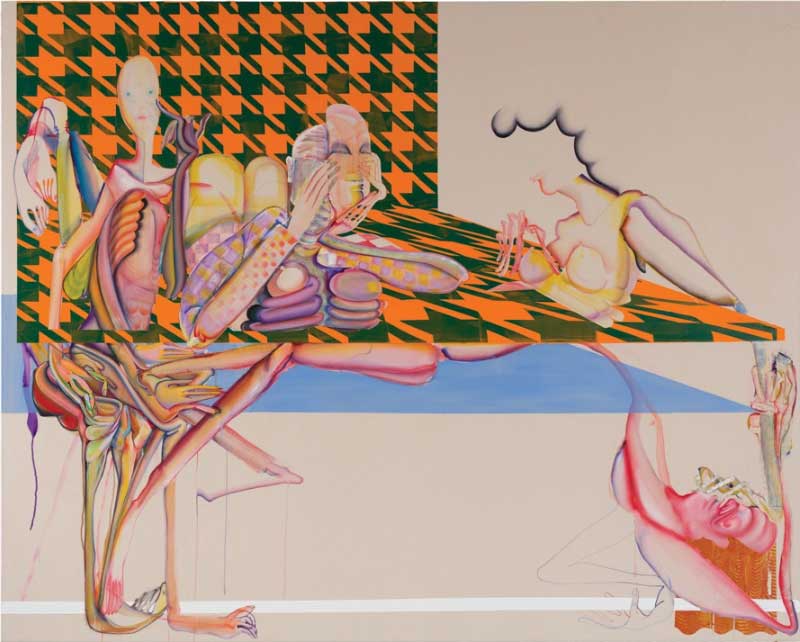

Figurative art has been hot for quite a few years now, but it’s always been widely popular. That’s partly because, for most people, art acts as a mirror in which they expect to see themselves and their world reflected back at them. Even when it represents unfamiliar subjects or experiences, figurative art facilitates this process of self-affirmation. It’s by differentiation that we come to know ourselves.

Putting that difference on display, however, can often be tokenistic. Recognizably Black or queer bodies in figurative painting, for instance, give collectors, galleries, and museums an opportunity to claim progressive politics at the expense of artists whose works may be intended to communicate far more than the external fact of their sexuality or skin color. This flattening of artists’ identities has been a troubling trend of the past couple of decades, and one which many artists are actively pushing against. The market has tended to classify art as “queer,” for instance, because it represents sex between bodies of the same gender, even though queerness encompasses more than sex.