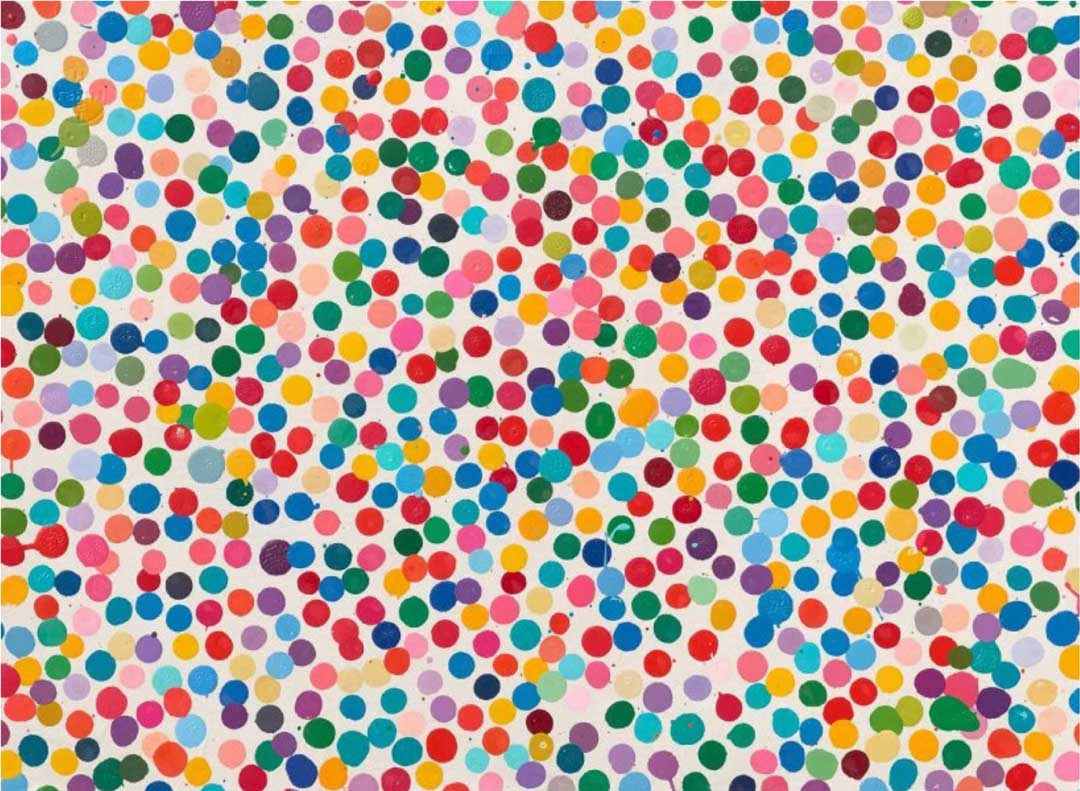

The Currency by Damien Hirst

Collectors of Damien Hirst are not allowed to own both the digital NFT and physical copy of his artwork ‘The Currency’, priced at 2,000 USD each. They can only choose one type among the 10,000 unique paintings. If they chose the NFT copy, the British artist will burn the physical one and vice-versa on a daily basis starting September 2022. Each of the 10,000 NFTs corresponds to the original work on paper manually done by the artist. Hirst and gallery HENI will hold an exhibition this year to burn the 10,000 NFT and physical artworks of ‘The Currency’. Buyers can decide whether they will keep the digital art or the physical copy of his public artwork only until 3PM BST today. The gallery reminds everyone who wants to participate that the whole process is a one-way exchange and to ‘choose wisely.’

The Currency is the first NFT collection of Damien Hirst, presented by HENI. The British artist, who is famed for his formaldehyde sculptures and installations, has mentioned his openness to adopting new technologies, and NFT piqued his interest about four years ago. He decided to put forward The Currency as his entrance to digital art, which challenges the concept of value through money and art. Ever a provocative artist, Hirst toys with the idea of daring his audience on the perception of value and how it affects their overall decision. With the time limit being imposed, he tests the boundaries between physical and digital art and how a collector uses their art and currency in modern times.