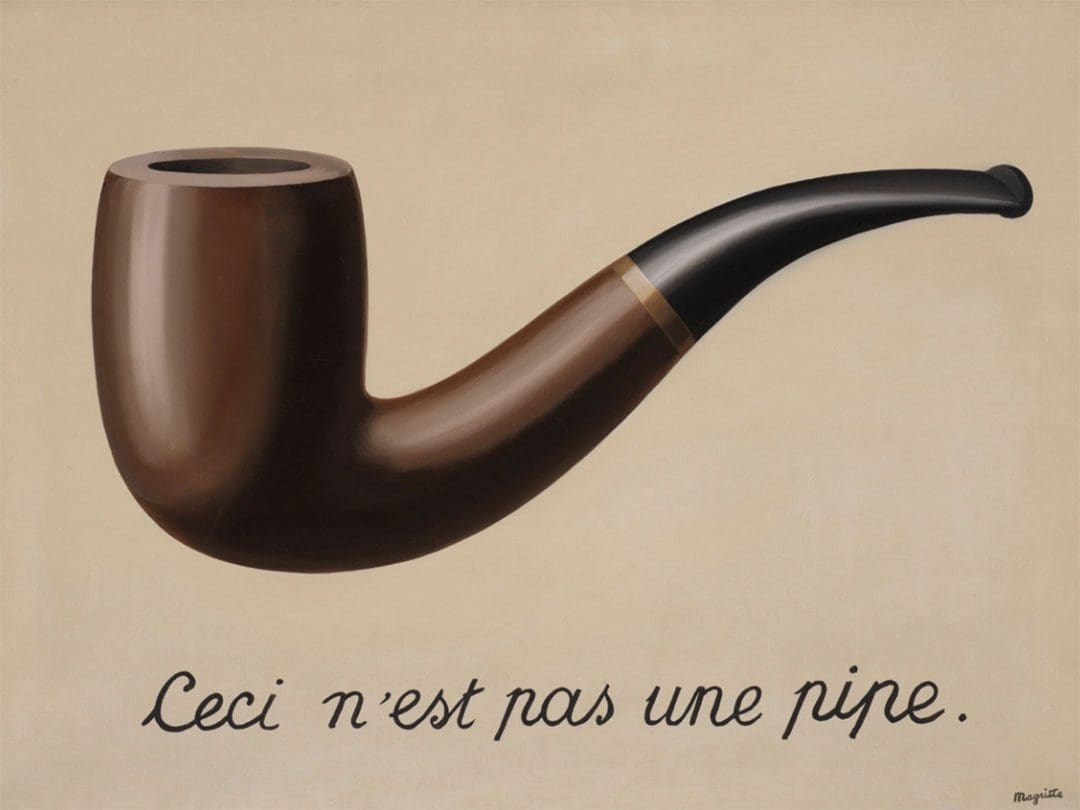

René Magritte, The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe), 1929, oil on canvas, 25 3/8 x 37 inches.

COPYRIGHT © ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK. DIGITAL IMAGE © COPYRIGHT MUSEUM ASSOCIATES / LACMA. LICENSED BY ART RESOURCE, NEW YORK.

In the meticulously rendered paintings of René Magritte, nothing’s really as it seems. The Belgian Surrealist famously insisted, for instance, in his painting The Treachery of Images (1928–1929) that the pipe it depicts was not actually a pipe, inscribing Ceci n’est pas une pipe in cursive letters below it.

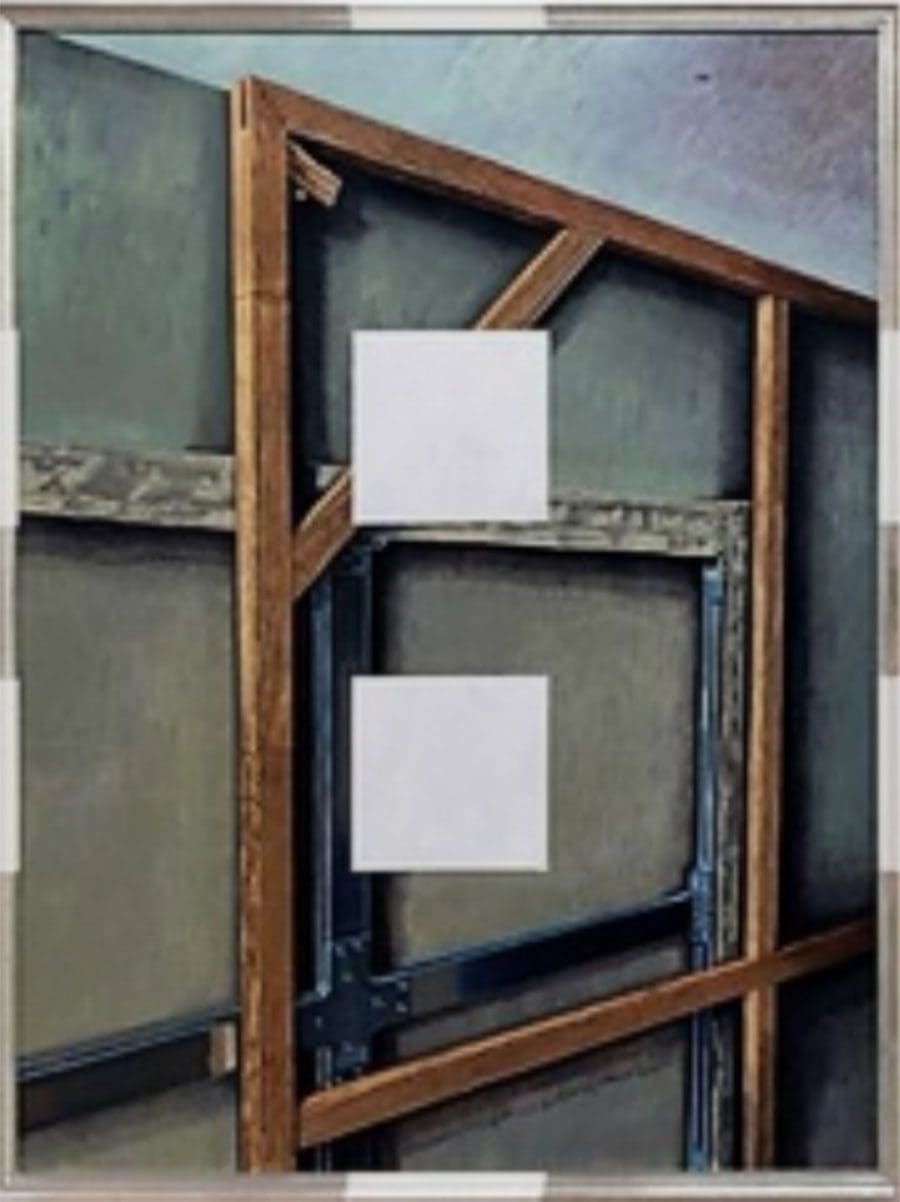

Through his art, Magritte contended that appearances are deceptive. Making viewers and artists scratch their heads since his 20th-century heyday, Magritte’s enigmatic images portray everyday things in uncanny ways. A bright daytime sky might blaze above a street at dusk, a country landscape may actually be a canvas, and the blue of an eye could just be a reflection of an azure sky. “Everything we see hides another thing,” said Magritte in an interview toward the end of his life. “We always want to see what is hidden by what we see, but it is impossible.”

What we do see in his work is a deliberate lack of painterliness; his canvases are flatly realistic, deflecting our interest in their execution. Instead, our attention is held by the strangeness of what’s depicted.

![Artist Shares Secrets of How To Draw Incredibly Realistic Portraits [Interview]](https://artistvenu.studio/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Screenshot_242-150x150.jpg)