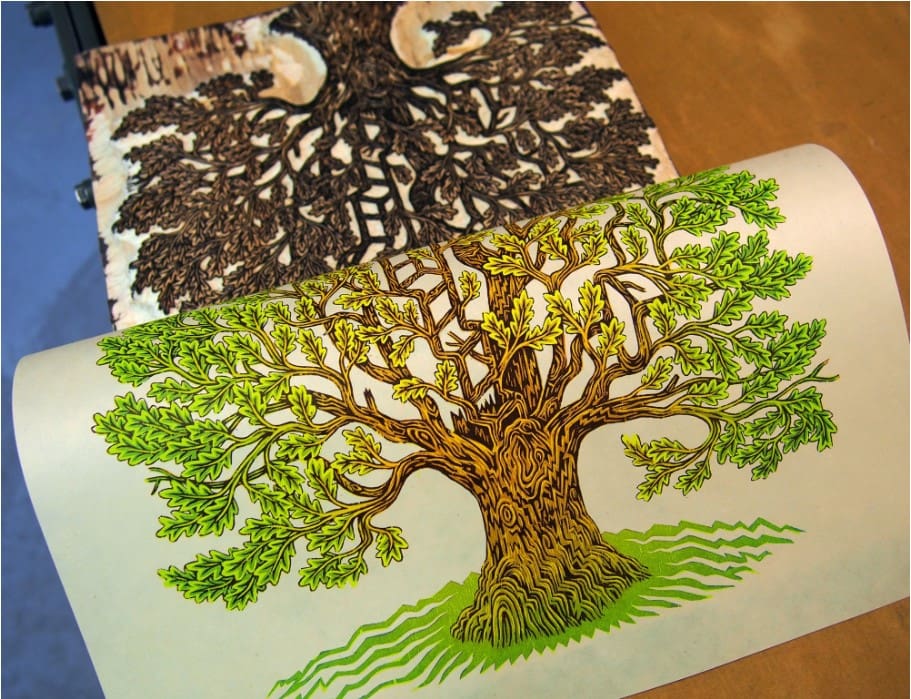

Featured image: “Midnight” (2024), acrylic on wood, 20 x 24 inches image © Gigi Chen

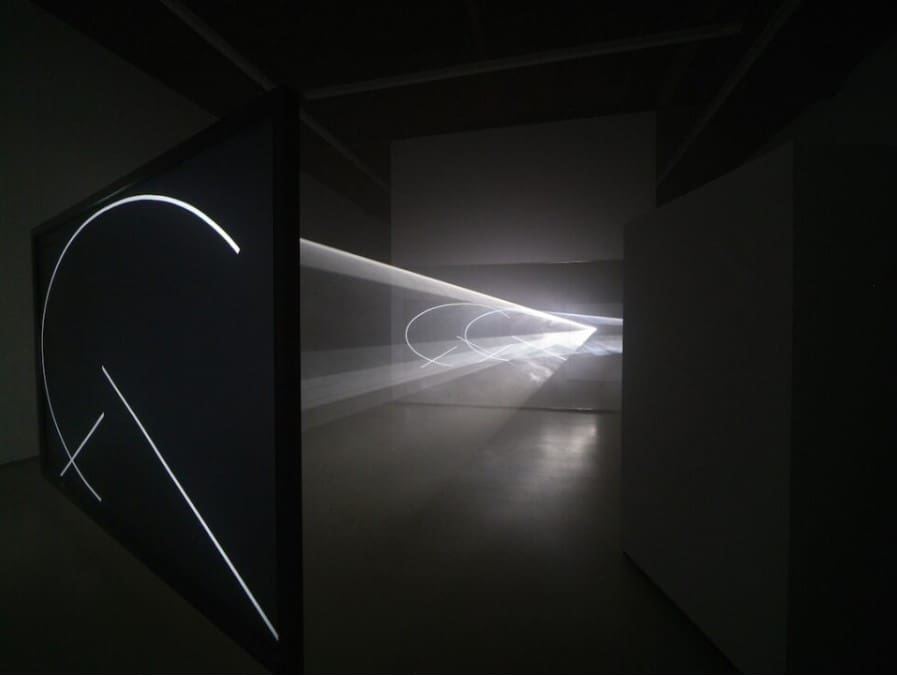

Bluebirds are often associated with happiness, love, hope, and positivity, making them an apt subject for New York-based artist Gigi Chen (previously), whose surreal paintings of wildlife merge the animal kingdom with symbols of home, comfort, and connection.

In her forthcoming solo exhibition A Collective Glow at Beinart Gallery in Melbourne, Chen continues to explore emotional ties between animals and the environment. In “A Sparrow’s Song,” a bird’s body radiates with neon pink hearts, while in “A Collective Glow,” half a dozen house sparrows stitch up a gleaming cavity in a pigeon’s breast.

![Artist Shares Secrets of How To Draw Incredibly Realistic Portraits [Interview]](https://artistvenu.studio/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Screenshot_242-150x150.jpg)