Dr. Monika L. Gloviczki was born in Poland. She studied medicine in Warsaw and in Paris, at the Faculty of Medicine – CHU Necker-Enfants Malades, where she earned her MD and PhD title.

In 2007, she moved to the United States and joined Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, where she worked until 2013.

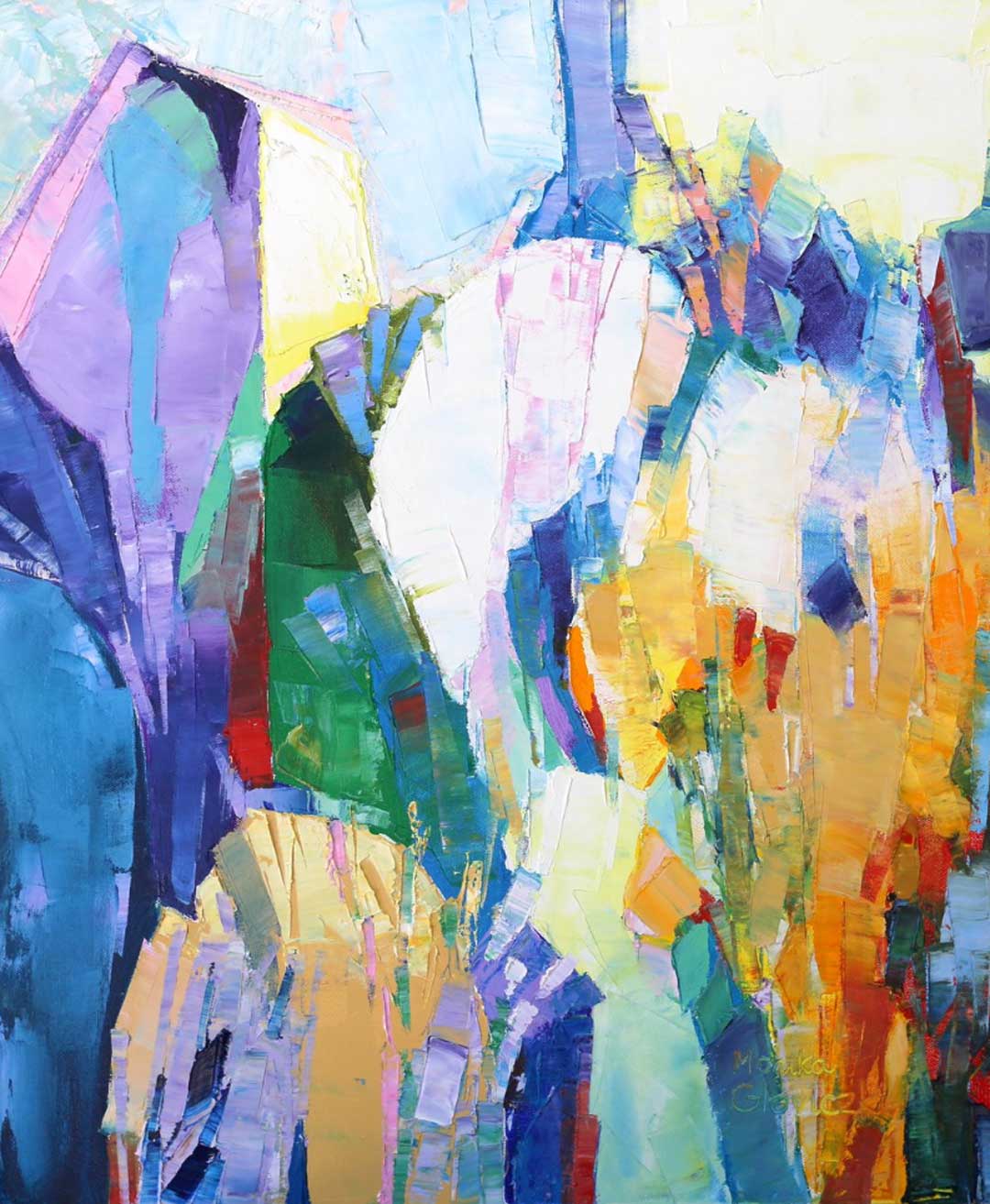

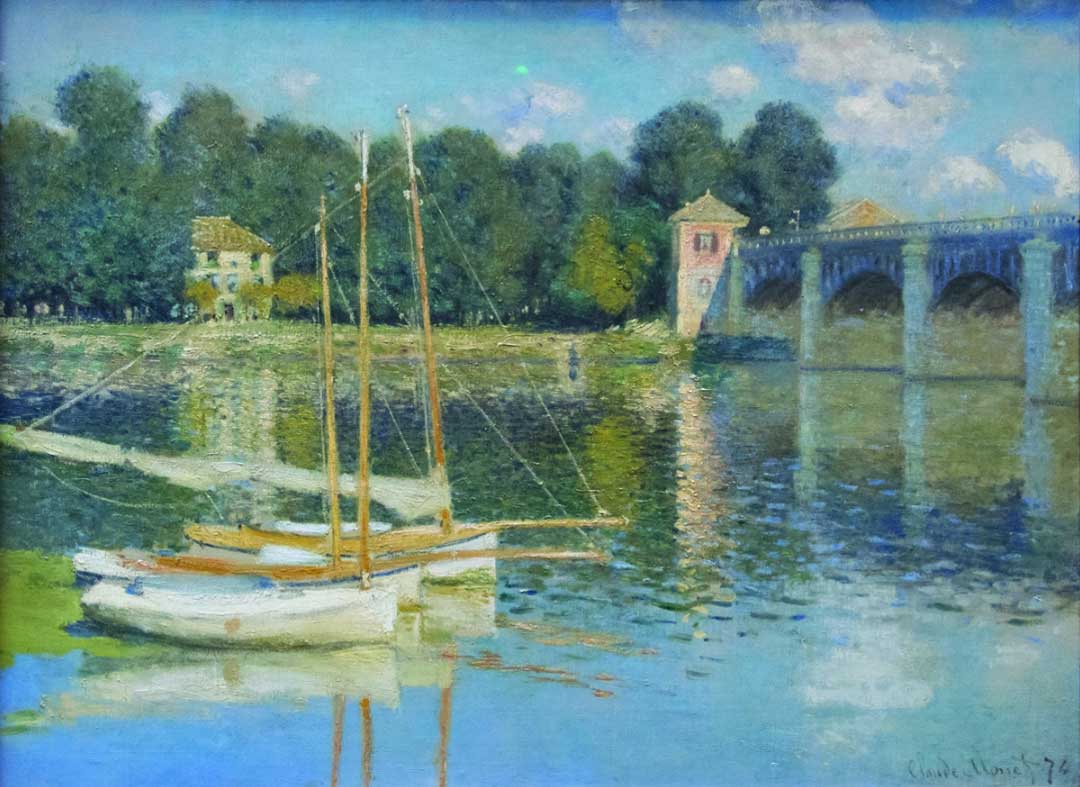

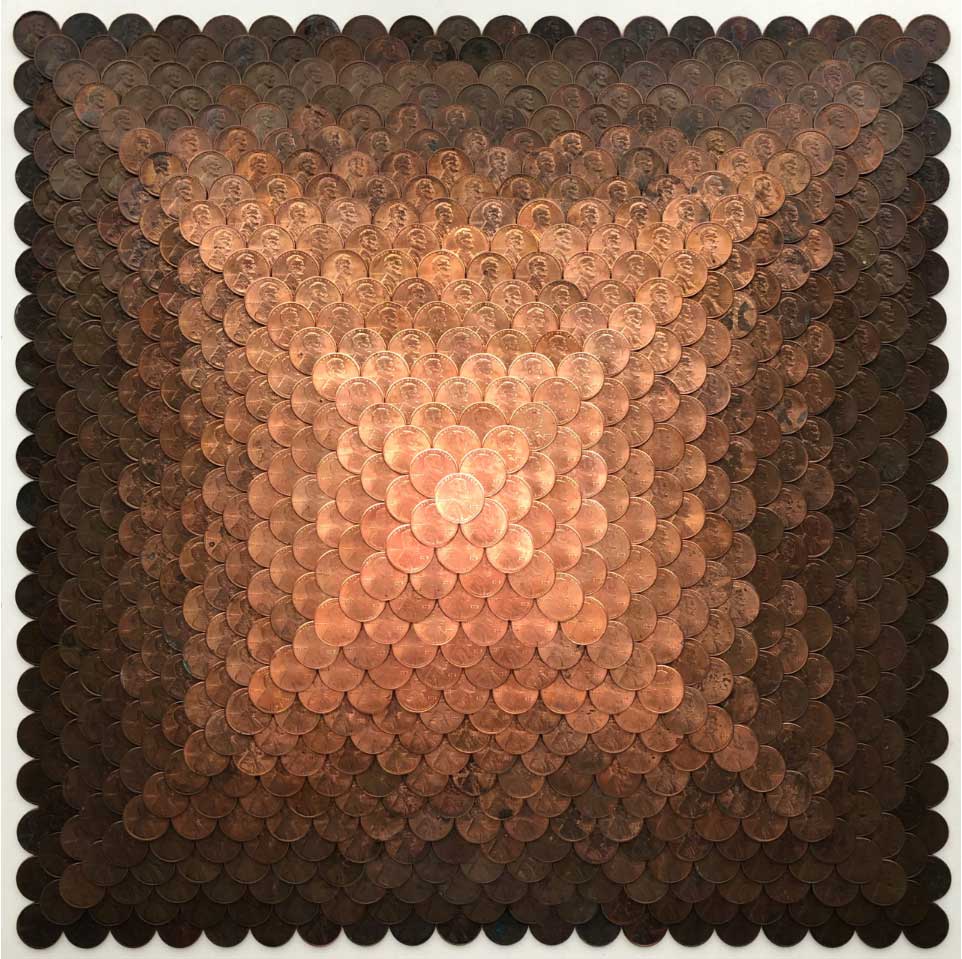

Gloviczki’s artistic education begun at an early age with her father, Stanislaw Kazmierczyk, a Polish artist painter and illustrator, who taught her basics of drawings, gouache, and oil painting. She also followed classes of drawings and paintings in Warsaw and later in Paris, at the Ateliers du Carrousel du Louvre. In the US she attended a two-year colourists’ school class. Since 2013, Monika Gloviczki has been a recognized painter, exhibiting regularly. She has had 33 group exhibitions, most in the US but also in France, Italy, and Azerbaijan. Among the shows the most important to be mentioned are the annual exhibitions at “Agora Gallery” in New York, NY, from 2016 to present; three exhibitions at M.A.D.S. Art Gallery in Milano, Italy in 2021; the “Art 3F” Art fair in Paris from 2018 to 2020 and the “19th Salon International d’Art Contemporain” in Paris, in 2016. Her works belong to private and public collections in the US and in France.