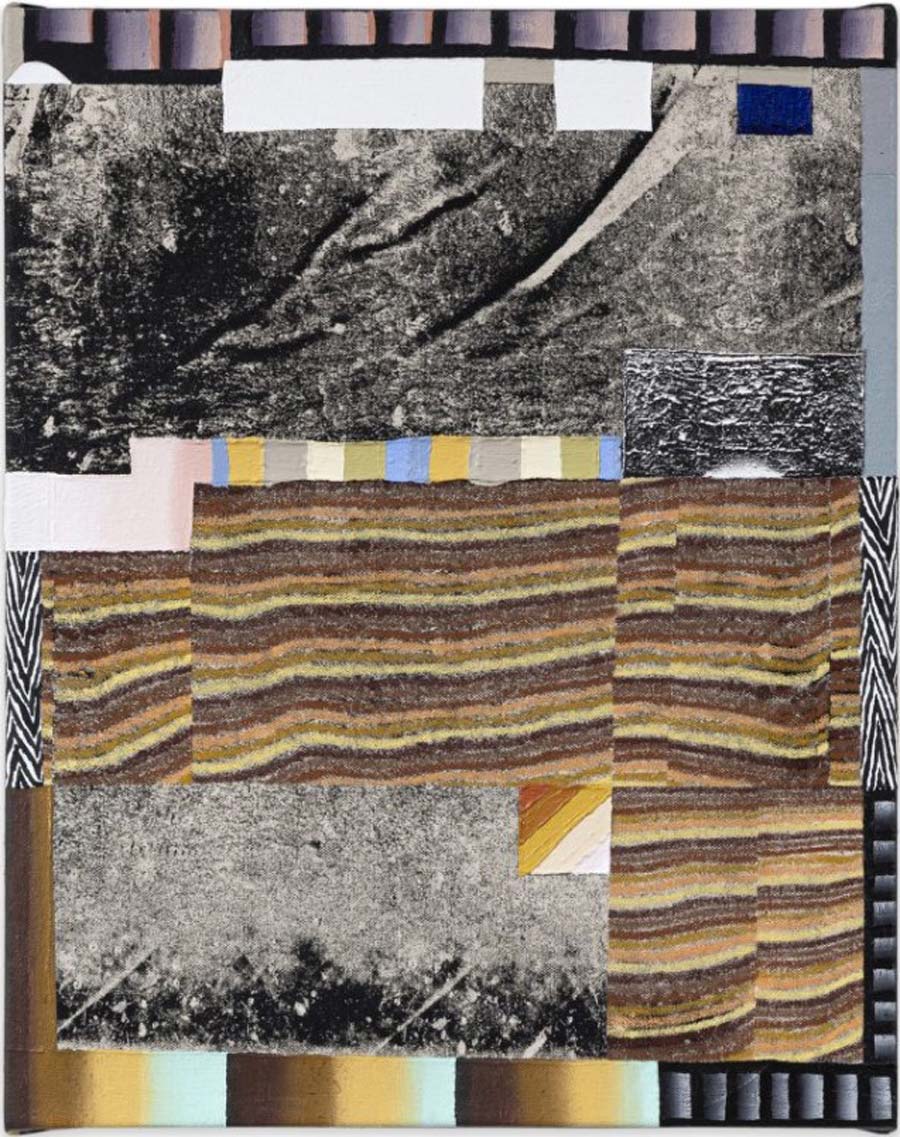

Featured image: Sarah Grilo, “Pines, Ochres and Green” (1963), oil on canvas, 44 x 50 inches (© The Estate of Sarah Grilo; image courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.)

Among the 17 paintings by artist Sarah Grilo in Galerie Lelong’s The New York Years, 1962–1970, one work most dramatically prophesizes the dread-inducing news alerts of our time. The brushwork in beiges, browns, greens, and grays in “America’s going…” (1967) is overlain by red lettering that the artist transferred from newspapers, eerily resembling those red chyrons that flash on our phones and stream across cable news today.

Born in Argentina in 1917, Grilo was creating introspective art amid social and political unrest well before she moved to New York. Through the group Artistas Modernos de la Argentina, she became an important painter amid the male-dominated Buenos Aires art scene of the 1950s, singled out for her monochromatic, geometric, and expressionistic approaches to lyrical abstraction.

Read the original article here… and return to share your comments below.

![Artist Shares Secrets of How To Draw Incredibly Realistic Portraits [Interview]](https://artistvenu.studio/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Screenshot_242-150x150.jpg)