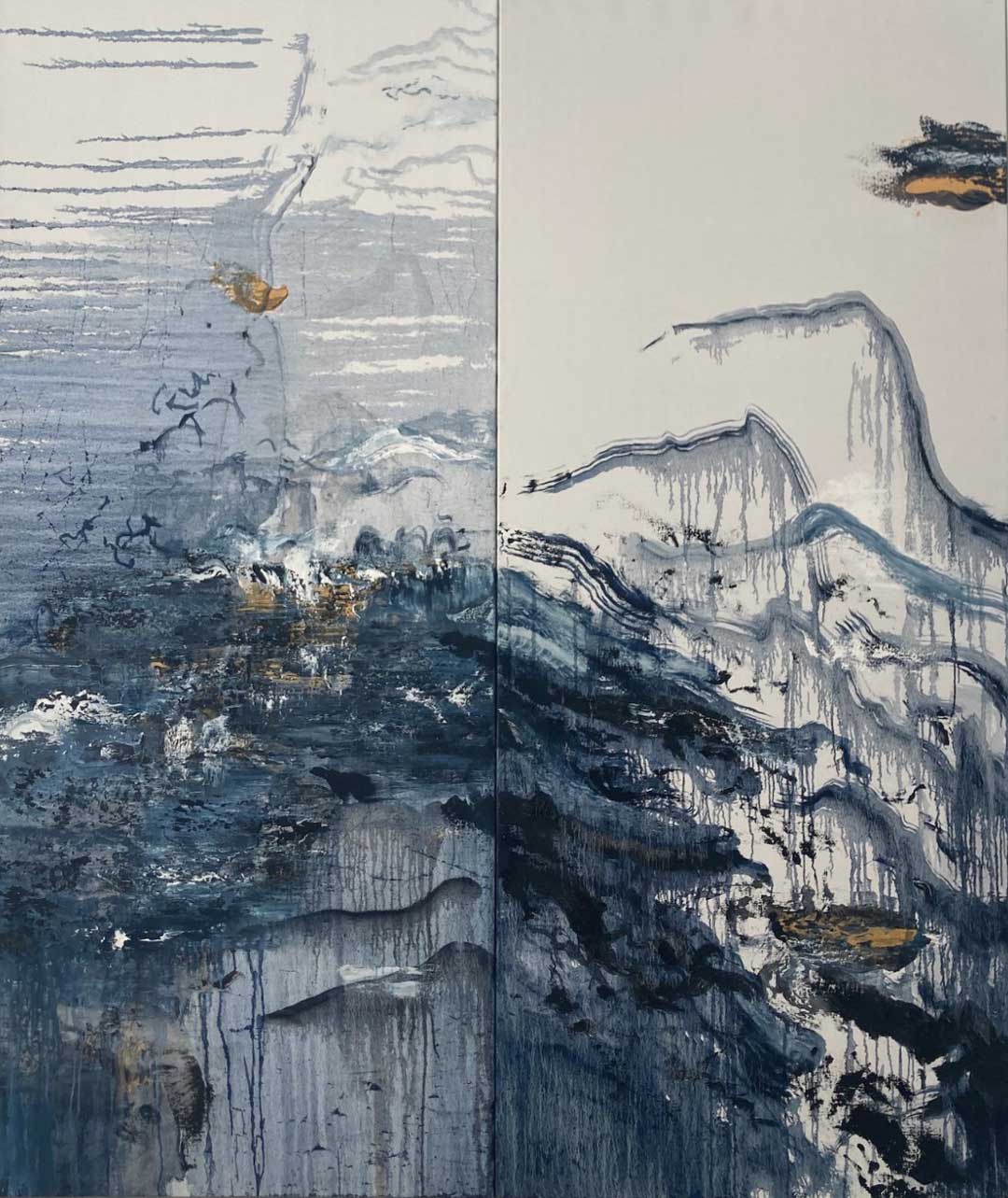

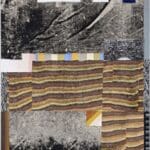

Maggi Hambling, “The last baboon” (2018) oil on canvas, 67 x 48 inches

I first learned of Maggi Hambling from her polarizing public sculptures. A bust of writer Oscar Wilde lounges in a green granite coffin, smoking a cigarette and laughing at passersby behind St. Martins in the Field in London. A nude, silvered bronze statue of 18th-century feminist thinker Mary Wollstonecraft emerges from an undulating silver plinth, whose sides jut out like free-floating hips, in North London. There’s an irreverence to those sculptures, a cheekiness that refuses one-dimensional worship. But there’s nothing cheeky about Real Time, her first exhibition in New York City, now on view at Marlborough Gallery. Instead, the swirling, gestural, and surprisingly moving landscapes, seascapes, and portraits offer more somber reflections on climate change and death.

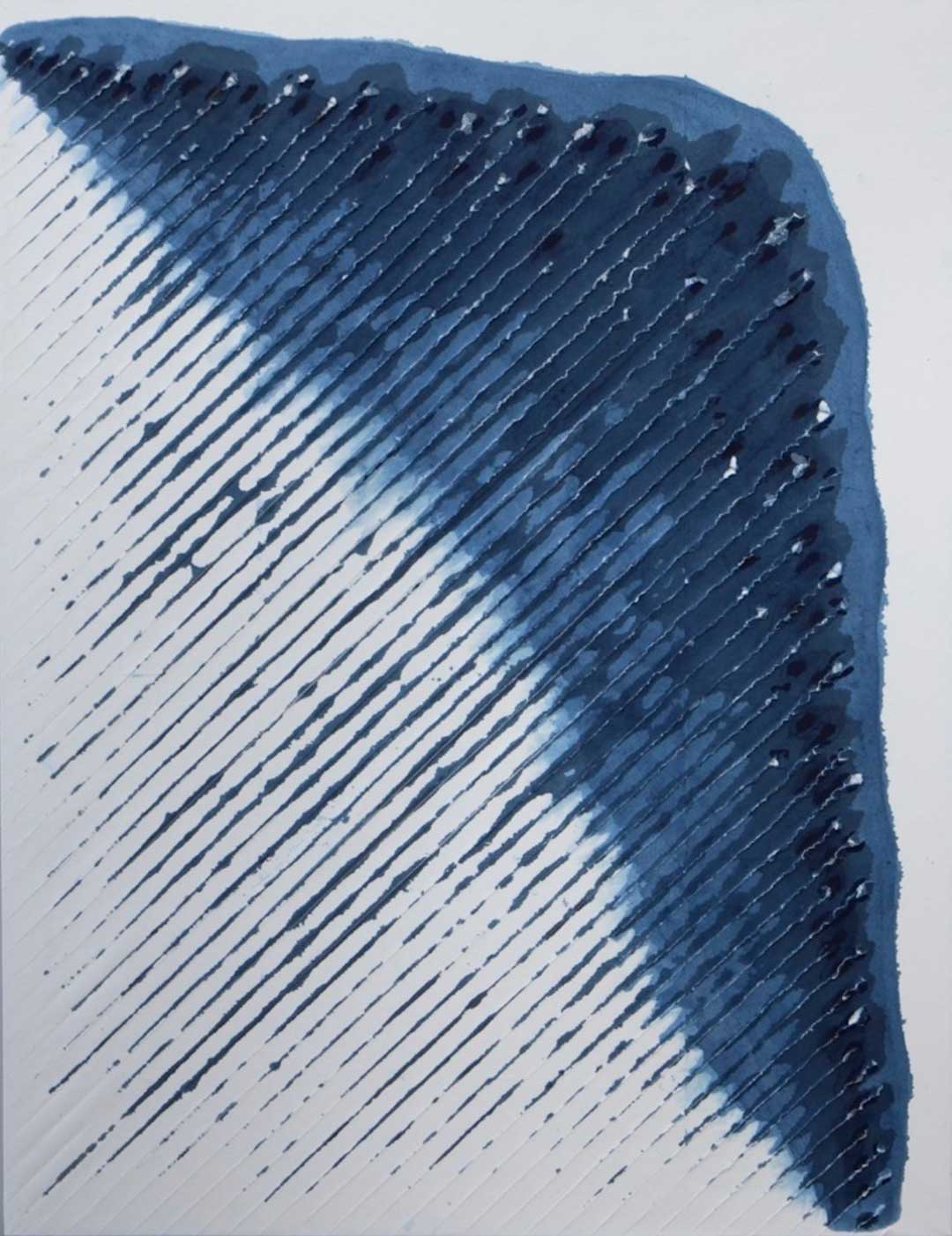

In indigo, black, and gray, Hambling’s paintings blend elements of abstract action painting with unmistakable representations of mountains, rivers, and animals.