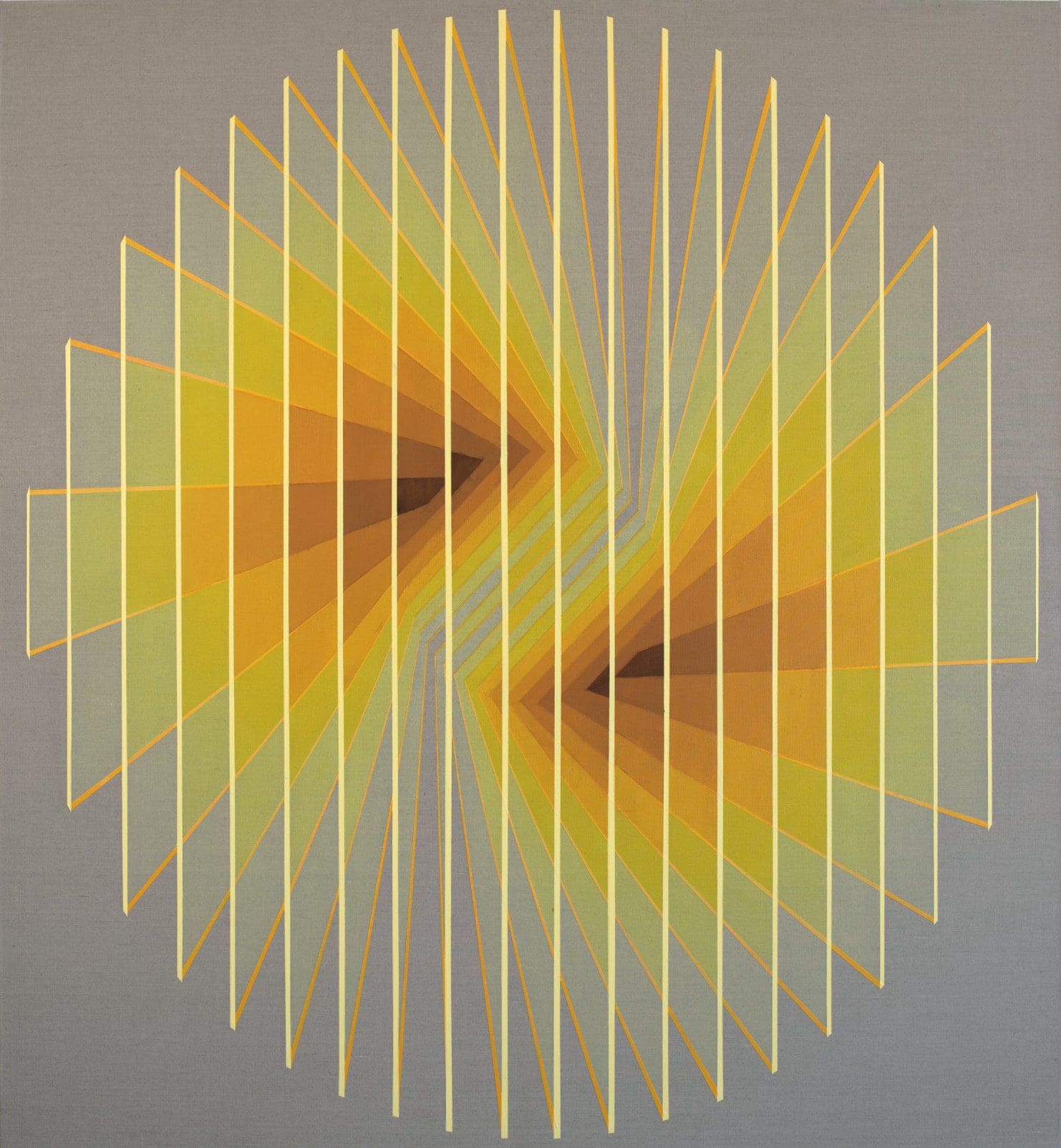

“Future Monuments 10.” All images © Daniel Mullen

What are the visual impacts of converging planes of color? This question is central to Scottish artist Daniel Mullen’s most recent series of paintings, which displays stacks of thin, rectangular sheets in exacting, abstract structures. “I am looking more at Rothko’s body of work and studying the vibrations of color and the almost alchemic effect that his work has on the sense,” the Rotterdam-based artist tells Colossal.

Comprised of meticulous angles and lines on linen, the acrylic paintings are studies of precision, geometry, and perception, allowing each element to collide in a mathematically aligned composition.