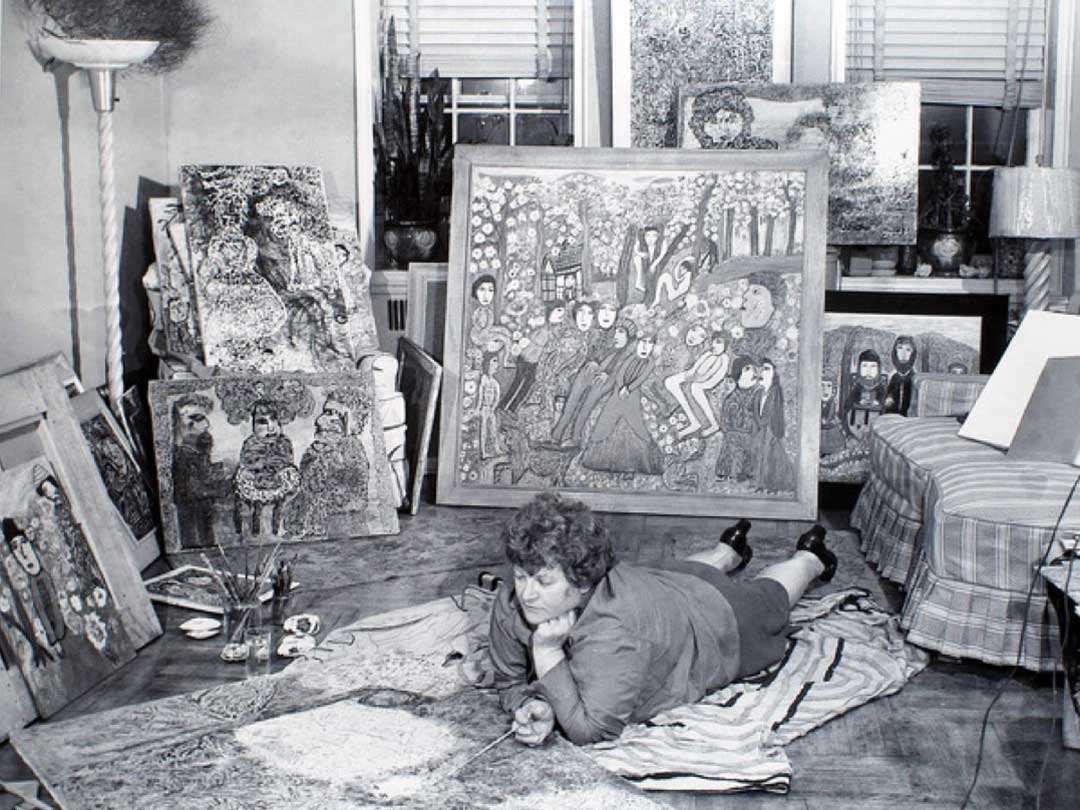

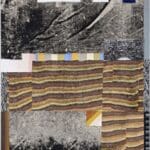

Detail of Rosaire Appel, “Backtalk”

Henri Michaux, Cy Twombly, and Xu Bing are widely celebrated for their explorations of asemic writing (writing with no semantic value), utilizing traditional materials and processes, such as ink on paper, oil painting, and woodblock prints. What these and many other creators of asemic works share is the use of the hand to make configurations that are linked to drawing and writing, but are not exactly either one. One extraordinary exception to this reliance on the hand is Rosaire Appel, who makes her work from digital files, which she prints on paper or clear acetate, sometimes on both sides. Subsequently, she will go back into these prints with ink and crayon, making each iteration unique. In addition to the sequential form of a comic strip, Appel has incorporated musical scores, as her interest is in structures that shape abstract elements, such as disparate visual languages and sounds. The result is a diverse body of work done largely in book form.

Rosaire Appel: Abstract Comics, her debut show at Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects, presents another side of this artist’s eye-catching work. The six works (five pigment prints with ink and crayon additions and a two-panel laser print on acetate with acrylic backing) are either tall and narrow, like a Chinese ink painting, or short and wide, like a comic strip or scroll painting, but she has no need to develop a signature style as a comic-strip artist does.