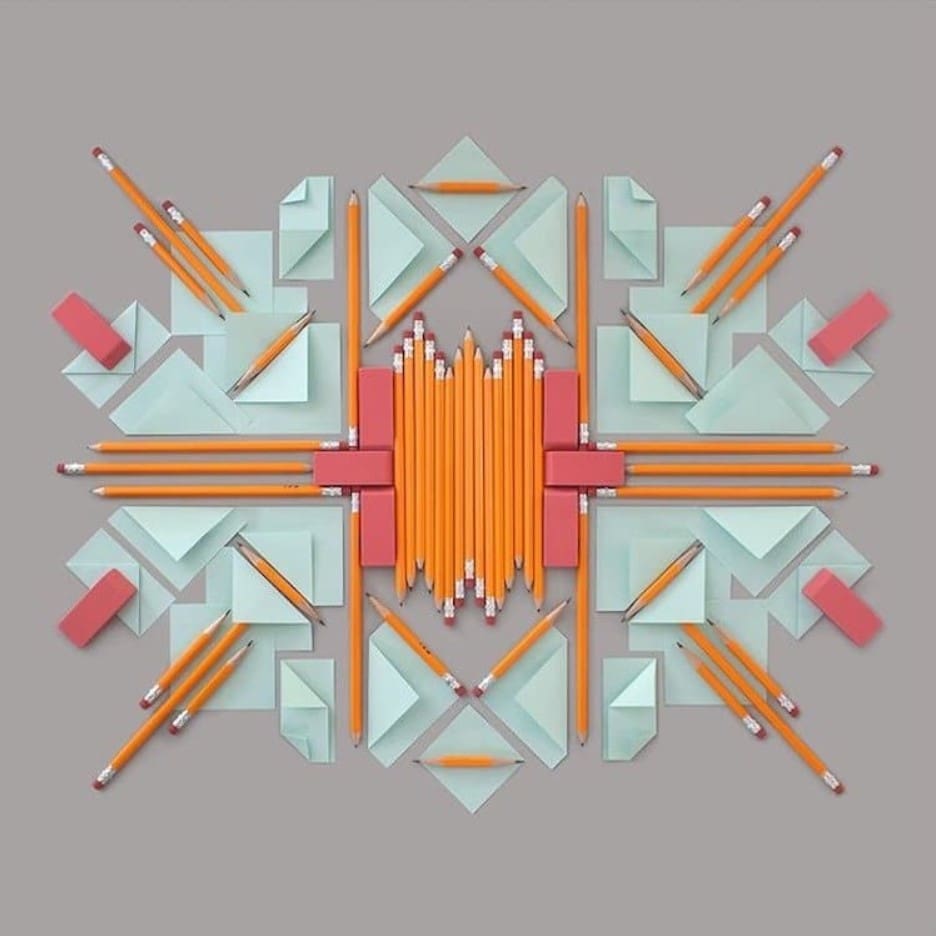

Leaves, fruits, and even butterflies come together to form unexpectedly beautiful arrangements in Kristen Meyer‘s art. The Connecticut-based prop stylist and designer specializes in geometric flat lays containing dozens of different objects. They are laid out in evenly spaced patterns until they form stunning designs that look computer-made.

The choice of materials in Meyer’s flat lays varies as much as the final shape. Her work includes everything from pencils and sticky notes to scraps of trash. However, the way she makes them appealing is always the same. After collecting the chosen materials, she modifies them as necessary so she can fit them into planned patterns. This might require cutting items with scissors or knives as well as carefully tearing the edges. Regardless of the method, Meyer makes sure that the alterations fit seamlessly with the design she has in mind. For instance, cuts of watermelon are carved into circles and half-circles and placed accordingly on a pastel-colored background.

Read the original article here… and return to discuss on artistvenu below

![Artist Shares Secrets of How To Draw Incredibly Realistic Portraits [Interview]](https://artistvenu.studio/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Screenshot_242-150x150.jpg)