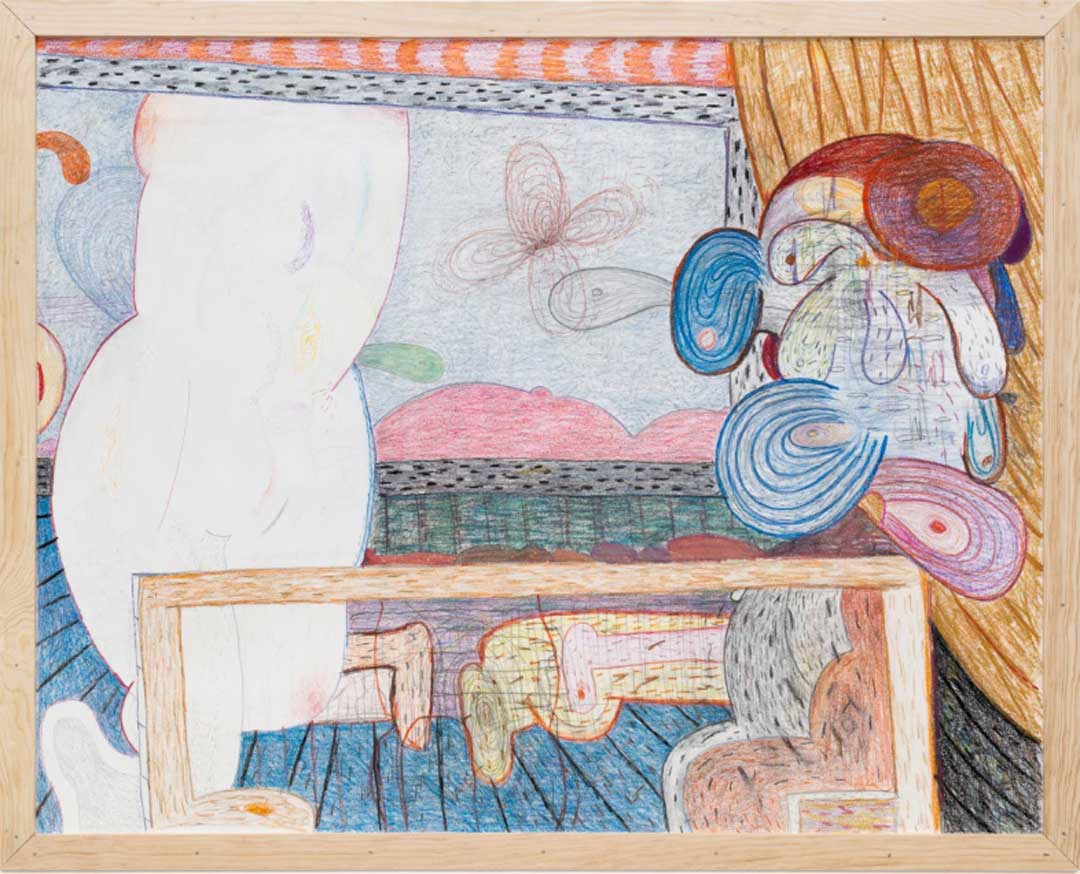

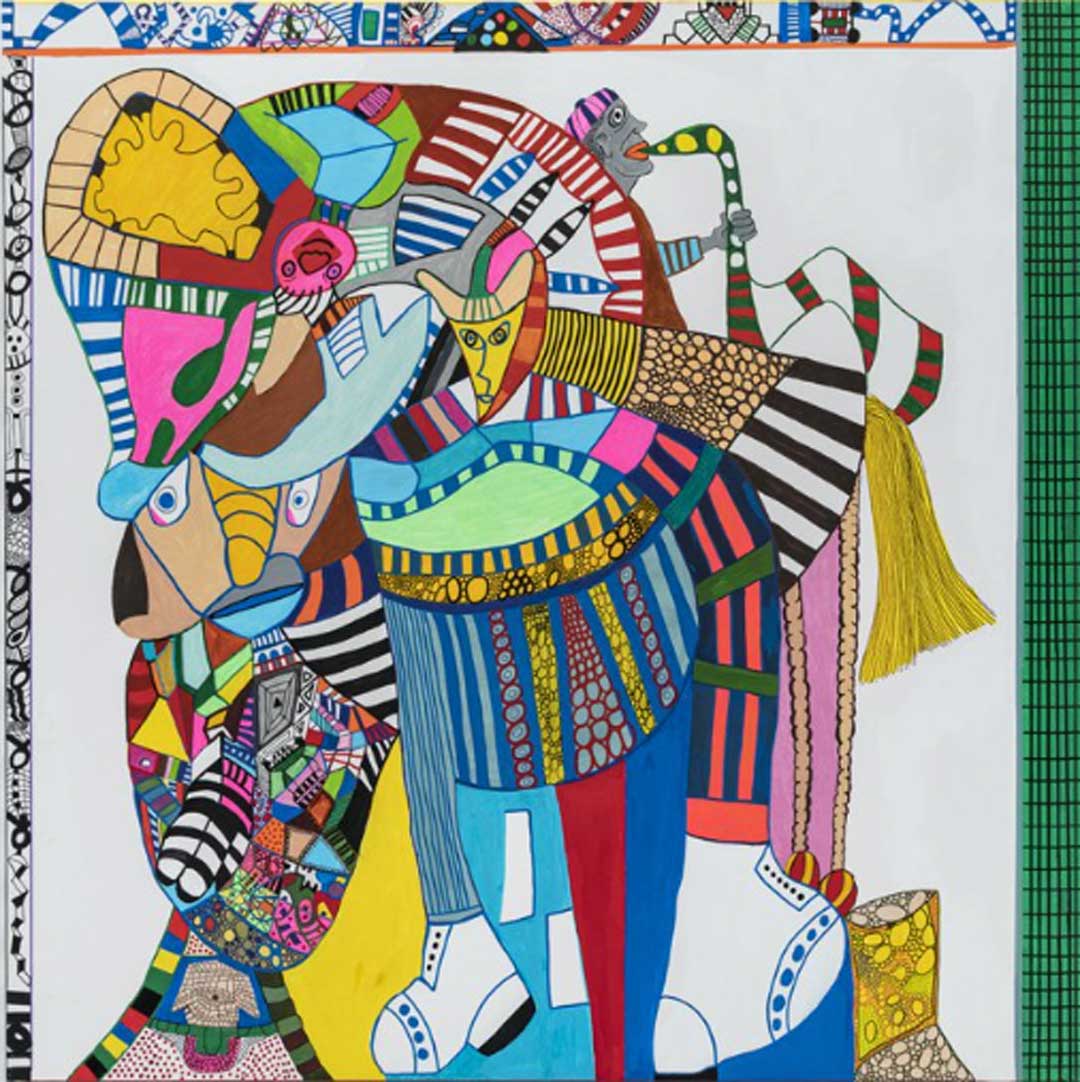

Richard Hull, “Teller” (2023)

CHICAGO — I first saw Richard Hull’s work in 1981 when he had his second New York show at the Phyllis Kind Gallery. We lost touch around the time Phyllis closed her gallery in 2009, and did not see each other again until 2016, when I wrote about visiting his studio in Chicago, where he has lived since the late 1970s. On my recent trip to Chicago, I did not think I would be able to see, much less write about, his current exhibition, Richard Hull: Mirror and Bone, at Western Exhibitions, running through April 22. I had not considered writing about Hull’s work because we were about to collaborate on monotypes at Manneken Press in Bloomington, Illinois — something we had never done before.